Shohin display in North American Pavilion

The National Bonsai & Penjing Museum is the world's first and finest bonsai museum, and its permanent collections are a part of our humanity’s history. We invite you to explore the Museum’s large collection of bonsai and penjing trees and their related art forms. And, plan a visit soon!

LEARN MORE:

Click image to enlarge.

“Every bonsai tells a story and some of the stories are truly amazing. From such humble beginnings to symbols of peace and perseverance they quietly stand on display as testaments to mans reverence toward nature.

”

japanese collection

The Japanese Collection began with the gift of 53 bonsai from Japan on the occasion of the American Bicentennial in 1976. The trees, which were from private collections, were selected by the Nippon Bonsai Association with financial assistance given by the Japan Foundation.

John Creech, Arboretum Director, speaks at the dedication ceremony for the Japanese Bonsai collection on July 9, 1976. Henry Kissinger, Secretary of State, is seated in middle at right.

The trees arrived in early 1975 in the United States and spent a year in quarantine at Glenn Dale, Maryland. On July 19, 1976, the collection was dedicated in a ceremony attended by many dignitaries from both countries. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was the featured speaker and accepted the gift on behalf of the United States.

The complete story on this gift of trees can be found in the NBF publication: The Bonsai Saga: How The Bicentennial Collection Came to America by former U.S. National Arboretum Director, Dr. John Creech. This book was published as part of the 25th Anniversary celebration of the Museum. You can also read more here in the history of the Museum section.

The collection, now numbering 63 trees, is on display from April through October in the Japanese Pavilion that was designed by Masao Kinoshita of Sasaki Associates. In the winter months the trees can be viewed in the Dr. Yee-sun Wu Chinese Pavilion.

The Japanese Pavilion’s 2018 renovations

CHINESE COLLECTION

Chinese Pavilion at the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum

Early construction of the Chinese Pavilion

The Chinese Collection at the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum resides in the Yee-sun Wu Chinese Garden Pavilion. This pavilion is named in honor of Dr. Yee-sun Wu (1905-1995) who was a Hong Kong collector of penjing.

In 1996 the pavilion was dedicated and a sign over the entrance in Chinese calligraphy states: “Dr. Yee-sun Wu – A place where plants are trained and cultivated under the hand of a man of letters.”

Penjing, the antecedent art form of bonsai, can be dated back to the Tsin Dynasty in China (265-420 A.D.). There are many schools of penjing and Dr. Wu was a proponent of the Lingnan School and maintained a collection of over 300 trees.

Janet Lanman

In 1983, Janet Lanman, a NBF Board Member, approached Dr. Wu with the suggestion that penjing should be included in the Museum’s collection. Dr. Wu agreed and he graciously offered trees to the Museum and funding for a Pavilion to house them.

In 1988, U.S. National Arboretum Director, Dr. H. Marc Cathey accepted the gift and referred to the Museum for the first time as: “The National Bonsai & Penjing Museum.”

There are now 36 trees in the Chinese collection and work is underway to add new trees in coming years.

1996 Dedication of the Chinese Pavilion and the International Pavilion & Exhibits Wing - left to right Curator Robert Drechsler, H. William Merritt, donor, Mary Mrose, International Pavilion & Exhibits Wing donor, Dr. Floyd Horn, Director of ARS, NBF Executive Director, MaryAnn Orlando and NBF President Dr. Frederick Ballard.

→ Visit the collection yourself. Plan your visit here.

The North American Collection

North American Pavilion interior

The North American Collection is displayed in the John Y. Naka North American Pavilion and the tropical species of these trees are found in the Haruo Kaneshiro Tropical Conservatory. All of the 63 trees that make up the collection are the work of people who live in North America.

The North American Pavilion was dedicated in 1990 and it honors the work of North American Master bonsai artist, John Y. Naka (1914-2004). His world famous forest planting “Goshin” is prominently displayed at the entrance to the pavilion. The trees of this collection are on exhibit in the Pavilion from Spring until Fall. In the winter months they can be viewed in the Chinese Pavilion.

John Naka pictured with "Goshin" at the entrance to the Upper Courtyard (2003)

The Tropical Conservatory was completed in 1993 and is named for “Papa” Kaneshiro (1907-1991) who was known as the father of bonsai in Hawaii. The tropical trees are on display throughout the year in the Conservatory except for the summer months when they are moved to the North American Pavilion.

→ Visit the collection yourself. Plan your visit here.

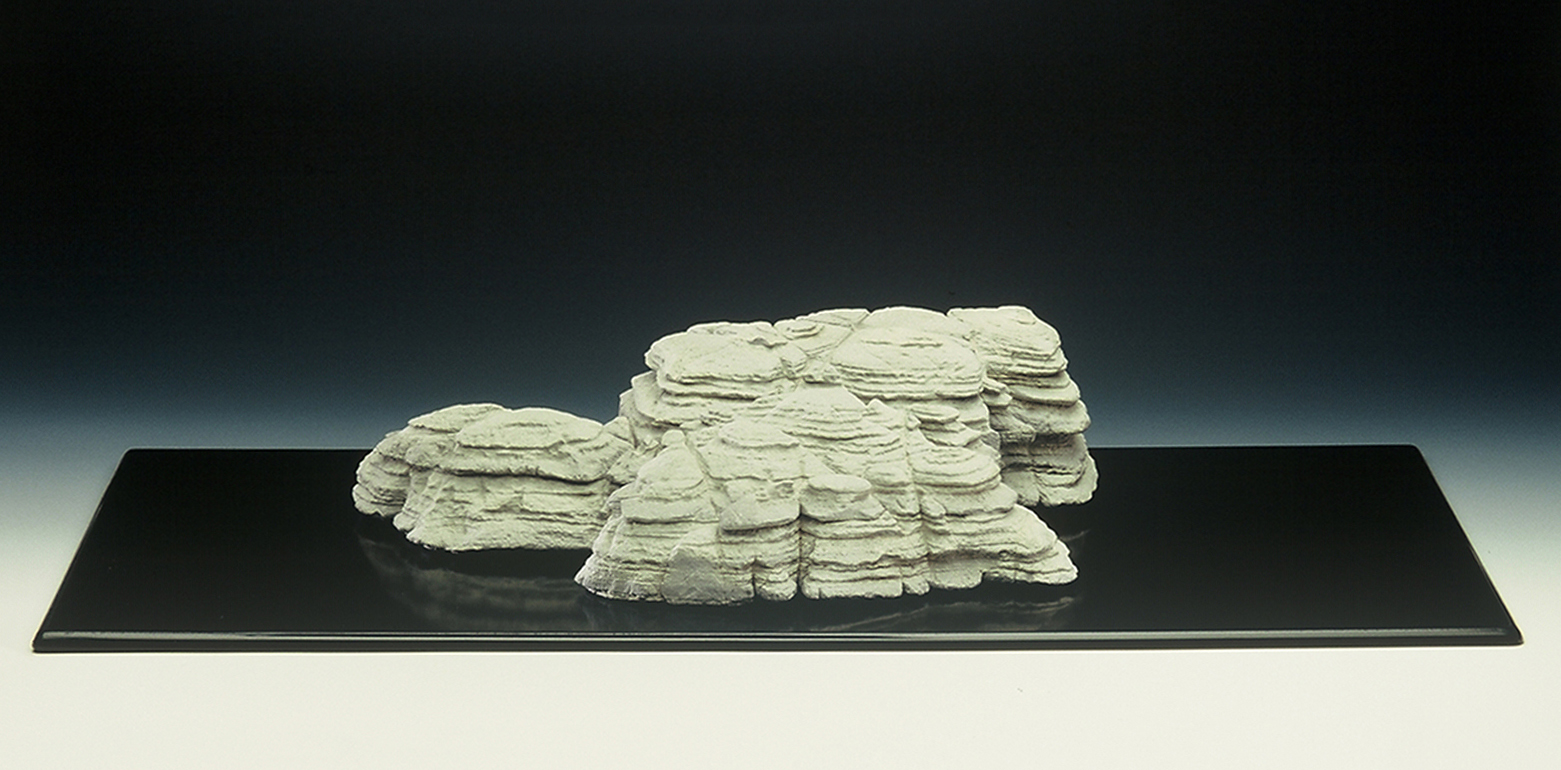

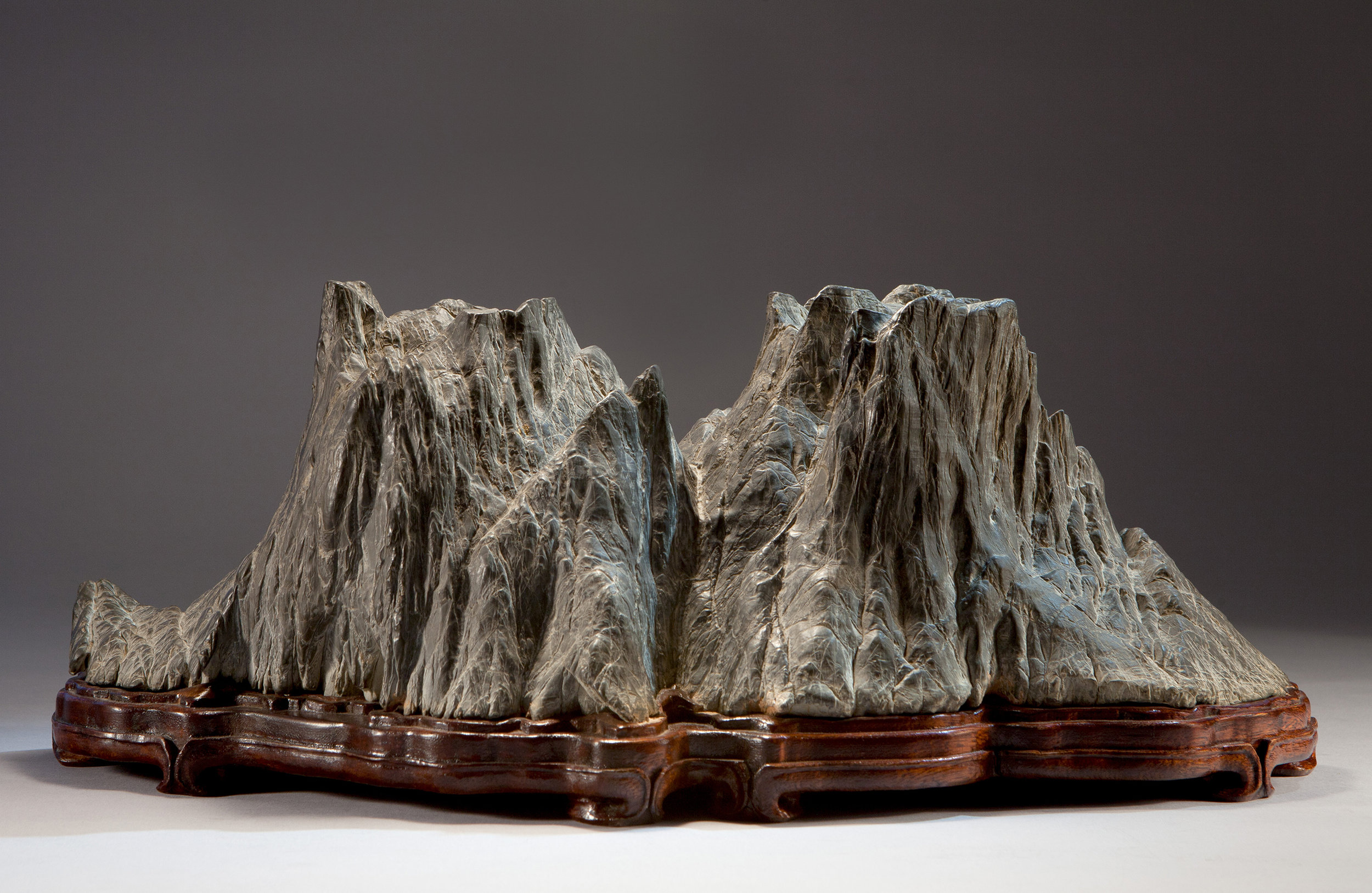

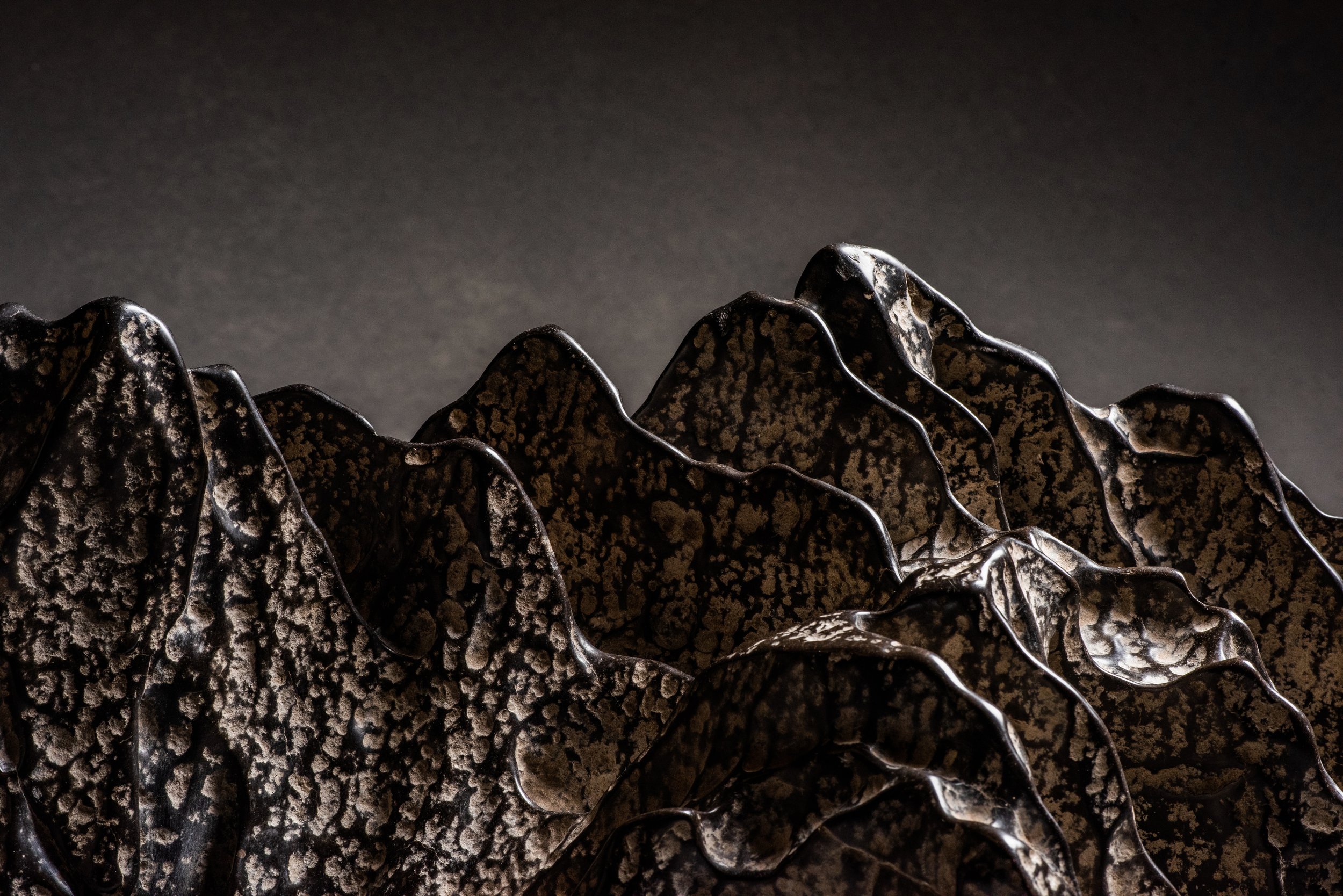

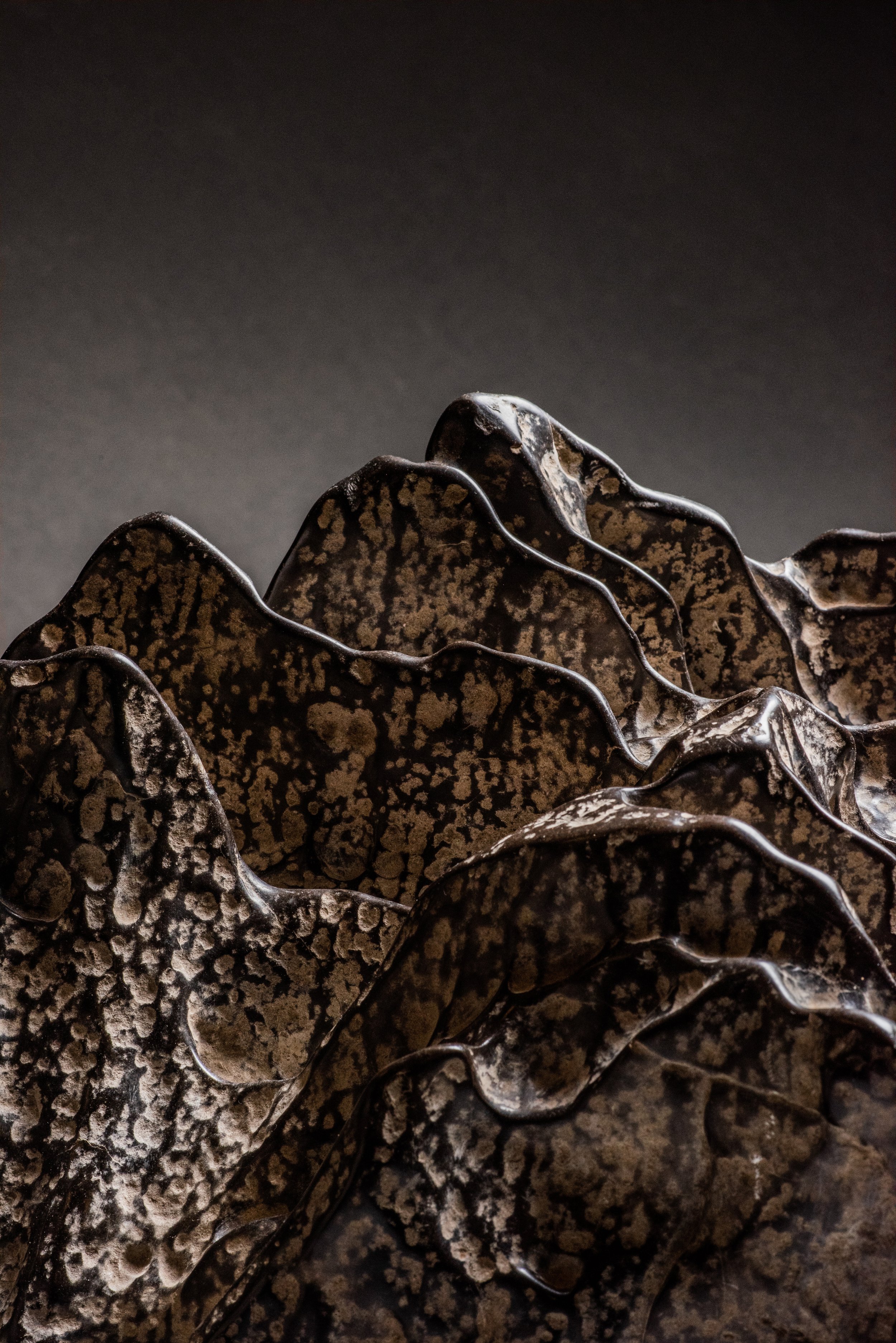

Viewing Stones Collection

The Museum is well known for its display of masterpiece living specimens of bonsai and penjing. A lesser known jewel is the Museum’s world-class collection of viewing stones.

Bonsai and viewing stones are closely related art forms, each reflecting a deep respect for nature. While a bonsai is cultivated to evoke the qualities of a venerable old tree, a viewing stone is usually displayed to suggest an aspect of the natural landscape, such as a distant mountain or a waterfall. Thus, when these small-scale forms are viewed together in a complementary arrangement, the whole of nature can be imagined.

The collection began with six Japanese viewing stones that accompanied the gift of bonsai from Japan on the occasion of the American Bicentennial in 1976. Today there are 105 stones from different countries: Japan, China, Indonesia, South Africa, Zaire, Namibia, Italy, Canada, and the United States. The viewing stone collection has expanded to include stones outside the formal requirements of Japanese viewing stones—such as Chinese scholars’ rocks and abstract natural stones.

Now Available!

This beautiful, in-depth book, which features the photography of Stephen Voss and elegant writings of Dr. Phillip E. Bloom, details the Chinese stones gifted by noted scholars’ rock expert Kemin Hu.

“A must-have volume for all students of Chinese stone appreciation.”

— Thomas S. Elias, Chairman of the Viewing Stone Association

Mary Mrose Exhibit Gallery at the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum

The stones are displayed in and around the Museum’s Mary Mrose Exhibit Gallery. Cases in The Melba Tucker Suiseki and Viewing Stone Display Area are periodically installed with different stones. The displays in the Japanese tokonoma (an alcove for art display in a Japanese home) and the Chinese scholar’s room provide a cultural context for the appreciation of different types of stones and related arts. The Special Exhibitions Wing provides a place for thematic exhibits which incorporate accessories in a more formal display.

→ Visit the collection yourself. Plan your visit here.

Pavilions, Courtyards, and Gardens

→ To learn more about the Construction and layout of the Museum, click here.

Logo wall

In addition to the three Pavilions and Tropical Conservatory used for display of the collections there are other wonderful spaces within the Museum complex. The lovely entrance area outside the first gate into the Museum is called the Ellen Gordon Allen Garden, named in honor of the founder of Chapter #1 of Ikebana International. Once through the gate the visitor is in a Japanese woodland garden shaded by large Japanese Cedars. This “Cryptomeria Walk” leads to the Maria Vanzant Upper Courtyard of the Museum.

The preeminent aspect of the Maria Vanzant Upper Courtyard is the dramatic logo wall, with moving water at the base and a large North American bonsai on exhibit throughout most of the year. The opposite side of the wall provides a backdrop for the display of smaller trees on stone plinths. The space is bordered by several planting beds, one of which has a stone stream, and another displays viewing stones given by Harry Hirao in memory of his wife, Chiyoko Alyce Hirao.

The International Pavilion, which serves as both a visitors center and exhibit space, is named in honor of a most generous and kindly benefactor of the Museum, Mary E. Mrose (1910-2003). This building includes both a Tokonoma for the display of bonsai, scrolls, stones and companion plants and a replica of a Chinese Scholar’s Studio, as well as a small library space. The Special Exhibits Wing of the building, constructed around a small interior courtyard, is used for changing exhibits of bonsai, viewing stones and ikebana.

The Kato Family Stroll Garden is entered from the Upper Courtyard through the H. William Merritt Gate. The pathway through this enchanting garden leads visitors to the Japanese Pavilion. Visitors can also descend to the Lower Courtyard to the Yee-sun Wu Chinese Pavilion. The Lower Courtyard, encircled by the Rose Family Garden, is attractive in every season of the year. Also in this space is the Melba Tucker Arbor that is used for educational displays and demonstrations by staff and volunteers.

Staff offices and work space, as well as a greenhouse, are at this level in the center named in memory of one of the most influential bonsai masters in the U.S., Yuji Yoshimura (1921-1997). Outside the center is a small bamboo bed with large vertical bamboo stones donated by members of the Potomac Viewing Stone Group.

The George Yamaguchi Garden of North American native plants fill the space between the Japanese Pavilion and the North American Pavilion, named in honor of the other renowned American bonsai master, John Y. Naka (1914-2004). The paths and gate in this area comprise the Final Phase of the Courtyard project that will make the entire Museum complex accessible to all visitors.

→ Visit the collection yourself. Plan your visit here.

SPECIAL TREES

All of our trees are special, but a few of them have a particularly special place in history. Here are their stories...

“YAMAKI PINE” (JAPANESE WHITE PINE CULTIVAR, PINUS PARVIFLORA ‘MIYAJIMA’)

Yamaki Pine

Visit the tree yourself. Plan your visit here.

There’s a book about this tree. Check it out here.

The story of the Japanese White Pine (also known as the Yamaki Pine, Pinus parvifolia, or “The Most Famous Bonsai in the World) has made its way around the world for generations. We could not be more proud to have this tree in our permanent collection, and it greets visitors when they enter into the Japanese Pavilion.

Yamaki brothers in front of bonsai tree

Why is it particularly special? It survived Hiroshima. Here is its story.

Thursday, March 8, 2001 was anything but a typical day at the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum. That morning two Japanese brothers landed at Dulles International Airport and, after checking into their hotel, headed straight to the Museum. Shigeru Yamaki, 21 years old, and his brother, Akira, 20, are the grandsons of the late bonsai master Masaru Yamaki, who in 1976 donated one of his most prized bonsai as part of Japan’s Bicentennial gift to the American people.

When the brothers arrived at the Museum, they approached one of the volunteers on duty that day, Yoshiko Tucker, asking her in Japanese for directions to where their grandfather’s bonsai might be found. Yoshiko and another volunteer, Michiko Hansen, quickly alerted Curator Warren Hill that important visitors had arrived. Warren then greeted the brothers and guided them to the magnificent Yamaki bonsai.

This Japanese white pine (Pinus parvifolia) is approximately 375 years old, and is the oldest specimen in the Japanese Bonsai Collection. Masaru Yamaki had made the gift of this bonsai before the brothers were born and so they had never seen it, although they were very familiar with it through photographs and family stories. As they stood respectfully in front of their grandfather’s ancient bonsai, Warren could not imagine the bonsai’s hidden past that was about to be revealed to him.

Yamaki grandson bows to the tree at the Museum. The tree and its roots are prepped for winter storage with a custom built wooden container.

Warren invited the two brothers to lunch. Yoshiko and Michiko also joined the group, and they translated the ensuing dialog with the brothers. The Museum’s records showed that the Yamaki bonsai had been donated by Masaru Yamaki of Hiroshima, but little was known about the donor or the history of the pine.

The brothers explained that their family had operated a commercial bonsai nursery in Hiroshima for several generations, but now the nursery is a private bonsai collection. Their father (Masaru’s son), Yasuo Yamaki, is a landscape architect and a member of the Hiroshima Prefectural Assembly; their mother, Michiko, is an artist. They live in the family home, which is adjacent to the bonsai garden. Former students of Masaru Yamaki now take care of the family’s large bonsai collection.

On the morning of August 6, 1945 at 8:15am the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

Shigeru said that all the family members (his grandparents and their young son-Shigeru’s father) were inside their home. The bomb exploded about three kilometers (less than two miles) from the family compound. The blast blew out all the glass windows in the home, and each member of the family was cut from the flying glass fragments. Miraculously, however, none of them suffered any permanent injury.

Pruning the Yamaki pine

Masaru Yamaki became a very influential member of the Japanese bonsai community, living until age 89. His widow, Ritsu Yamaki, is now 91 and still living in the family home with Shigeru’s father and mother.

Ritsu Yamaki

The great old Japanese white pine and a large number of other bonsai were sitting on benches in the garden. Amazingly, none of these bonsai was harmed by the blast either, because the nursery was protected by a tall wall. A Japanese broadcasting company would later film the bonsai garden and report on how the wall had saved the bonsai.

When Shigeru returned to Japan, he obtained from his father a wealth of information, including photographs, documenting the illustrious bonsai career of Masaru Yamaki. On September 1 of 2003, Shigeru came back to Washington, D.C., bringing with him copies of these invaluable historical materials. The Foundation hosted a luncheon in honor of Shigeru on September 3, 2003 attended by Warren Hill, Jack Sustic, Young Choe, Yoshimi Komiyama, Kazuma Maki (a friend of Shigeru from Japan), and Felix Laughlin.

Masaru Yamaki was proud to have given his Japanese white pine bonsai to the American people as part of Japan’s Bicentennial gift. (For the story behind the Bicentennial gift, see The Bonsai Saga-How the Bicentennial Collection Came to America by Dr. John Creech, published by the Foundation in 2001.) After the Japanese white pine arrived at the U.S. National Arboretum, he came to see it in its new home in the Japanese Pavilion at the Arboretum (now part of the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum).

Yamaki and Creech

Masaru Yamaki learned the art and science of bonsai from his father, Katsutaro Yamaki. After World War II, Masaru Yamaki was one of the leaders of the effort to revive bonsai as a commercial enterprise in Japan, and he served for many years as the director of a cooperative association that promoted the production of improved varieties of bonsai in the Hiroshima area.

He was well-known for his masterpiece Japanese black pines (Pinus thunbergii) as well as his Japanese white pines. Bill Valavanis visited Masaru Yamaki in 1970. He recalls being struck by Mr. Yamaki’s magnificent Japanese black pines with extremely heavy trunks planted in very small pots. This combination illustrated the technical knowledge and skill required to produce small feeder roots on a heavy trunk necessary to keep the tree living in a small container. He also remembers some very unusual Nishiki Japanese white pines having corky bark. Mr. Yamaki had one of the original cultivars.

Friends and family of Mr. Yamaki at Museum

Friends of Mr. Yamaki included the other leading figures in the bonsai world in Japan, such as Saburo Kato and Toshiji Yoshimura (father of Yuji Yoshimura). In 1983, he was awarded the prestigious “Yellow Ribbon Medal” by Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone-the first such award given to a member of the bonsai industry. To commemorate Mr. Yamaki’s receipt of the Yellow Ribbon Award, the famous sculptor, Katsuzo Entsuba (himself a recipient of the Order of Culture Award, the highest award given in Japan for contributions made in developing Japanese culture) produced a limited-edition cinnabar ink-seal bronze box.

The Yamaki pine is truly a testament to peace and beauty, and we are fortunate to realize the miracle of its survival in 1945.

We are very grateful to Shigeru Yamaki and his father, Yasuo Yamaki, for the most interesting information and photographs they have provided concerning the Yamaki bonsai and its donor, the bonsai master Masaru Yamaki.

Fast forward to 2003.

On Friday, May 9, 2003, the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum received an unexpected visit from Masaru Yamaki’s daughter, Mrs. Takako Yamaki Tatsuzaki. She and her husband Mr. Takashi Tatsuzaki, along with their son Jin, daughter Amaka, and their friends Mr. and Mrs. Takehisa Iizuka wanted to see a particular tree in the collection. The Museum had been under renovation and formally reopened only one day before the Tatsuzaki visit.

The visitors arrived late in the afternoon. The Museum was closed. Fortunately, they located Assistant Curator Jackson Tanner outside of the Museum’s gates. Despite a language barrier, Jackson soon realized they had a family relationship to a tree in the collection. He quickly arranged a private group viewing with Curator Jack Sustic and Assistant Curator Jim Hughes, who are the bonsai caretakers.

Photo left to right: curators Jim Hughes and Jack Sustic, Mrs. Takeko Yamaki Tatsuzaki, Mr. Jin Tatsuzaki, Mrs. Takehisa Iizuka, Ms. Amaki Tatsuzaki, Mr. Takehisa Iizuka, Mr. Takashi Tatsuzaki

The Curator recognized the Yamaki family name and led them through the entire Japanese Collection starting at its exit gate. They stopped at the entrance to the Collection and there was the family’s gift– Masaru Yamaki’s pine collected from Miyajima, almost 400 years old, maintained by the family for five generations, a survivor of the blast at Hiroshima, a gift to the American people. The tree now holds pride of place at the entrance to the Japanese Bonsai Collection at the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum. The tree is stunningly beautiful and healthy. Mrs. Tatsuzaki held a beaming smile, spoke rapidly to the others & patted the soil of the tree her father had tended.

“There was much pride in the pavilion that day.

Our visiting guests were proud of the pine and of being a part of its life. Jim and I were proud of the pine and of being a part of its life.

It is amazing to think how many lives this bonsai has touched. All the lives of the people that are no longer with us and all the lives it has yet to touch. I believe that these things help to shape the character of a bonsai as much as wiring and pruning do.”

Photo: NBF President Felix Laughlin presents a memento of her visit to Mrs. Takeko Yamaki Tatsuzaki as her husband (left) and NBF guest Mr. Hiromasa Oguchi joyfully observe.

The timing was fortuitous. Though totally unplanned, they had arrived on the day in which the Foundation held its annual board meeting and dinner. The National Bonsai Foundation was honored to invite them to attend its annual dinner that evening. The NBF dinner gave the American bonsai community an opportunity to meet Masaru Yamaki’s daughter and her family.

The dinner also gave Mrs. Tatsuzaki a chance to meet Hiromasa Oguchi, the son of another famous donor to the Museum, Kenichi Oguchi who in 1976 had donated the Shimpaku juniper that is used as the model for the Museum’s and Foundation’s logo. Thus, the daughter and son of two very special donors of the bonsai in the Japanese Collection were able to reminisce over a dinner, much to the delight of everyone present that evening.

Mrs. Tatsuzaki had vivid memories of the Yamaki pine from her childhood and could recollect playing in the garden where the bonsai had stood so majestically for so long and where it had survived the Hiroshima blast. She anticipates locating more documentation about the bonsai and its garden history in Japan, and it is eagerly awaited.