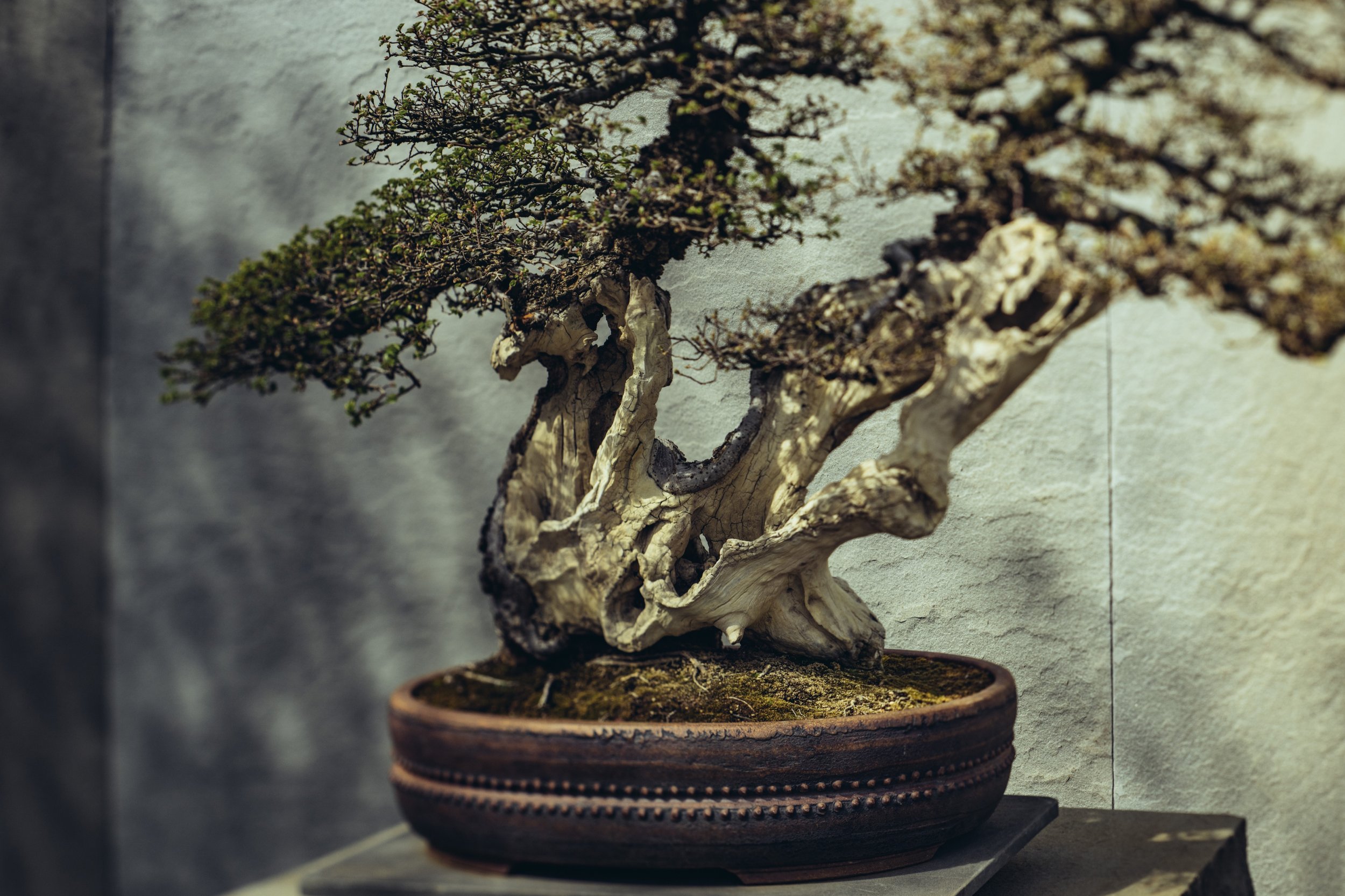

Clockwise from top left: Blue Spruce by Karen Harkaway; Western Hemlock by Nick Lenz, donated by Mike McCallion; Douglas Fir donated by Bjorn Bjorholm and Richard Le; Horseshoe suiseki from Seiji Morimae and Ronald Maggio; Crepe Myrtle from McNeal McDonnell, styled by Bjorn Bjorholm.

RECENT Donations to the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum

RECAP

Over the past few weeks, we’ve shared the stories behind the five remarkable additions to the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum’s collections. These gifts, from visionary bonsai artists and collectors, reflect the vibrant evolution of this traditional art and its expanding scope in North America.

Thanks to the generous donors, these bonsai and suiseki continue as a living legacy — one that will inspire, educate, and connect people through the power of natural art.

These pieces are far more than beautiful additions to the Museum’s renowned Japanese, Chinese, and North American collections. They represent an evolution that honors tradition while propelling the art of bonsai forward.

Each tree tells a story of American creativity rooted in carefully selected native species. The Douglas Fir, Blue Spruce, Crepe Myrtle, and Western Hemlock are not only emblematic of North America’s diverse landscapes, but also demonstrate how bonsai in this region is developing its own voice—one that values innovation while continuing to pay homage to its rich history.

The suiseki offers a moment of peaceful contemplation, presenting evocative symbolism of the earth and its waterways that reminds us of our deep connection to the natural world. It also stands as a symbol of connection, friendship, and the enduring bonds between cultures that have preserved and shared this art form across generations.

In case you missed the full series, here’s a look back at the impressive additions to the Museum in 2024. Click any of the images to enlarge, and click the links below to read the story of each one:

A beautiful Blue Spruce by Karen Harkaway, president of the American Bonsai Society;

A striking Douglas Fir, collected by Richard Le and cultivated by Bjorn Bjorholm;

An intricate Crepe Myrtle from McNeal McDonnell, styled by Bjorn Bjorholm;

A majestic Western Hemlock, created by innovative artist Nick Lenz and donated by Mike McCallion;

And a remarkable Horseshoe suiseki presented by Seiji Morimae on behalf of the family of Ronald Maggio.

In 2024, the Museum focused on North American artists, species, and collectors celebrating the growing influence of American bonsai within a global conversation. These additions remind us that bonsai is not static but constantly evolving, shaped by the hands of dedicated artists, curators, and supporters like you.

Arboretum Director Dr. Richard Olsen, Assistant Curator Andy Bello, Curator Michael James, and artist Dr. Karen Harkaway.

The generosity of donors makes it possible to preserve, care for, and share these living works of art with the world. Every gift supports the Museum’s mission to foster appreciation of bonsai as a cultural and artistic tradition, rooted in nature and alive with possibility.

NBF Board Member Ross Campbell, former PBA president Aaron Stratten, Curator Michael James, artist Bjorn Bjorholm, and NVBS president Roberto Coquis.

The National Bonsai Foundation is proud to help introduce these five remarkable specimens into the permanent collection at the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum. We extend our deepest gratitude to the artists and donors: Karen Harkaway, Richard Le, Bjorn Bjorholm, McNeal McDonnell, Nick Lenz, Mike McCallion, the family of Ronald Maggio, and Seiji Morimae.

We invite you to come see these new additions in person at the U.S. National Arboretum in Washington, D.C. — and to continue following these stories as they grow.

If you missed our original announcement, you can read the introductory blog.