Is it a penjing? Is it a bonsai? No – it’s a penzai!

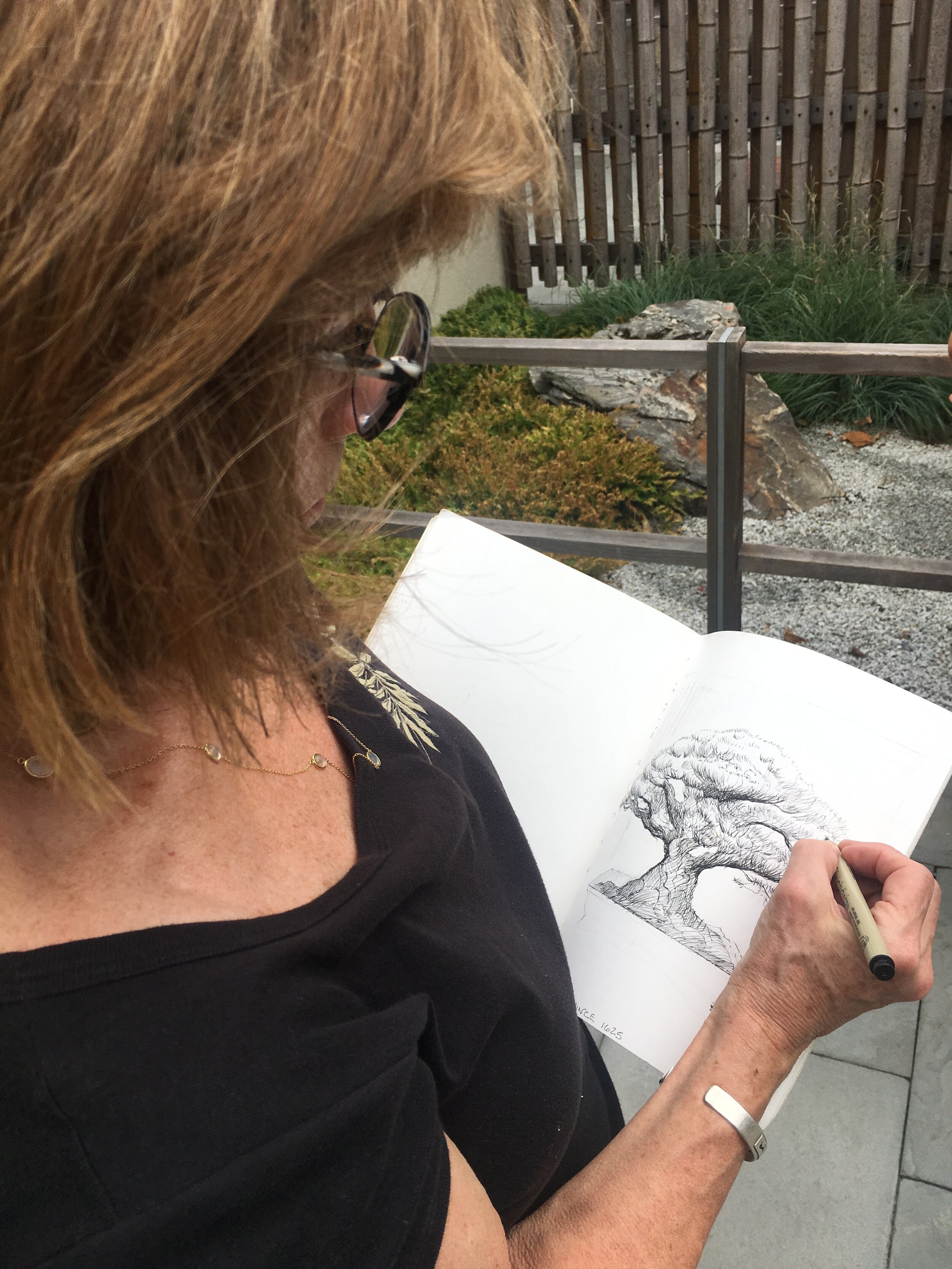

Many people are familiar with penjing and bonsai, but what happens when you fuse the styles together? This trident-maple – named for its trident-shaped leaves that turn red and gold in the fall – trained by local penjing master Stanley Chinn, is a great example.

While penjing usually depict scenes, bonsai are generally single trees. Chinn, who emigrated from China as a child, spent most of his life in Silver Spring, Maryland, fusing bonsai and penjing to form beautiful creations, like this maple.

After Chinn passed away in 2002, he left most of his collection to the National Bonsai Foundation, the non-profit branch that supports the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum. Former curator Jack Sustic chose 10 trees from the collection to keep at the Museum. Chinn’s trees are also on display at botanical gardens in Montreal and Brooklyn.

“He was very interested in the history of penjing and how it started, which happened way before bonsai ever reached Japan,” Museum curator Michael James said.

Not just a fan of the trees, Chinn loved spending his free time outdoors.

“If you ever wanted to find Stanley, you’d just go look in his backyard,” said James

Chinn trained the maple in the photo above to illustrate a Chinese dragon perched on a stone. James surmises that Chinn fused two trident maple seedlings together on the stone to create the configuration: one of the maple tree seedlings creates the dragon’s back and tail and the other seedling forms the creature’s neck and head.

“He was a master at the root-over-rock style, so he was really good at training little roots of seedlings down stones,” James said.

The tree represents the “dancing dragon” style of the Sichuan school of penjing.

“The different parts of the tree become representative of the dragon’s body,” he said. “The roots grasping the rock are the claws of the dragon, the branches become the bones or the body of the dragon and the leaves emulate dragon scales.”

James said Museum volunteers use techniques like defoliation to balance the tail and the head of the dragon.

“The two seedlings Chinn used either have different root systems or some genetic variation, so they grow at different rates,” he said. “The tail portion is a little more vigorous than the head portion, so at the Museum we have to prune it accordingly.”

Penjing arrangements categorized under the Sichuan style, which Chinn specialized in, are often characterized by their curvy branches and trunks, called “earthworm style.” James said Chinese artists used to use palm fiber to form exaggerated arcs that resemble the body of an earthworm.

“You just don’t see them in the Japanese collection like you do in his style,” James said. “You can just look through the Chinese collection and look at the trees and say, ‘Oh, that’s Stanley.’ He just did his own thing and it’s very evident in his work.”