Ross Campbell, NBF secretary/treasurer elect, pictured with his yew bonsai.

At the National Bonsai Foundation, we are grateful to our Board of Directors for their support, ingenuity and bonsai knowledge. Get to know the directors in our spotlight series, The Bonsai Board, highlighting their bonsai experience and why they joined NBF.

Read about Board Chair Jim Hughes here and Chair-Elect Dan Angelucci and Secretary/Treasurer Jim Brant here.

For this edition, we interviewed Ross Campbell, who joined NBF in August 2020 and became secretary/treasurer elect later in the year. Campbell worked for 34 years as a senior analyst for the U.S. Government Accountability Office, reviewing and evaluating programs at federal agencies. He has penned reports to Congress on topics like ecosystem management, invasive species control and honeybee health.

Campbell grew up in Detroit, Michigan, a Sister City to Toyota in the Aichi Prefecture of Japan. In an exchange program between the two cities, he traveled to Toyota to immerse himself in Japanese culture through tours, travel and staying with a Japanese family. He saw shrines, temples and examples of Japanese artistic hobbies, but he was most impressed by the combination of managed and natural styles in Japanese gardens.

“Just about everyone I came across, young or old, had some interest in a historical or cultural practice like ikebana or martial arts,” Campbell said. “They really put a lot of effort, energy and skill into each garden.”

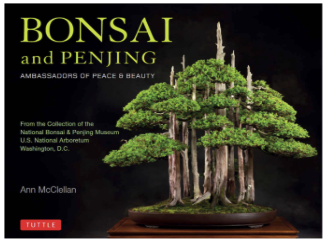

He moved to Washington, D.C. in 1985 and encountered the U.S. National Arboretum. The National Bonsai & Penjing Museum rekindled his interest in the art and culture he saw in Japan. Campbell then bought his first bonsai, a juniper sold at the Eastern Market on Capitol Hill.

He joined and eventually presided over the Washington Bonsai Club, which met at the Arboretum. Campbell is a Brookside Bonsai Society member and newsletter editor and served as the Potomac Bonsai Association treasurer for many years.

He said he is most drawn to bonsai because bonsai artists connect with nature, forests and trees in their natural setting. Campbell prefers more naturalistic bonsai styles rather than abstract – he wants his bonsai to be more representative, not suggestive, of real trees.

“You can’t exactly play with or tinker with an actual forest, but you can do that with a bonsai and try to put that large forest experience into something you can hold in your hands,” he said. “I can’t draw, I can't paint, but I’m hopeful that through this bonsai hobby I can develop some artistic skills.”

Campbell and his son Ian in front of John Naka’s Goshin. Campbell’s family took annual pictures in front of the tree to show how his son and the tree had grown.

Campbell enjoys both the group activity of bonsai and the relaxing practice of working one on one with his own bonsai.

“I enjoy being with people and seeing or talking about their techniques, but ultimately it is most satisfying for me to be making progress just me and the tree at home,” he said. “It takes your attention and concentration but allows you to shut out stress and difficulties, slowly letting the process unfold and seeing things change over the seasons and years.”

One of Campbell’s most memorable experiences at the Museum was when Curator Michael James asked him to help perform some maintenance on John Naka’s famous “Goshin” on Campbell’s second day as a volunteer at the Museum.

“It’s not like I had a pruning saw or even concave cutters in my hand, but the fact I was able to perform even minor work on such an important bonsai was very unexpected, fun and a bit tense,” he said.

In winter 2019, Campbell became a Museum volunteer to improve his bonsai technique and help the Museum continue to thrive.

“People who don’t know anything about bonsai come through the Museum but are clearly captivated by the collections,” he said. “NBF keeps that opportunity available, and if I can do anything to help NBF or the Museum, then that’s what I want to do. I’m glad I’ve been able to support the Museum as a visitor and now as a board member.”